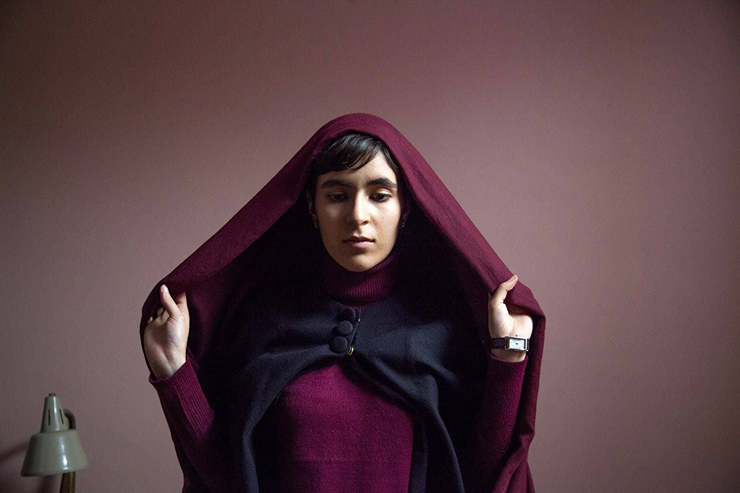

Mahour Jabbari.

“Ava,” a gripping drama set in Iran, lures viewers into its world of full body veils and rigid norms with carefully crafted scenes of domestic life. It sits back and observes from a distance as its teenage protagonist exchanges pleasantries and bickers with her parents. It depicts her headstrong attempts to rock the boat when she sees the future she'd envisioned for herself threatened, not only by institutional forces that would seek to control her, but also by those she loves the most.

Then it gradually turns the screws on her, and the audience, as it traces the insidious attempts to silence an outspoken girl whose only transgression is behaving like an adolescent. Think of Jane Austen's “Emma,” then add fundamentalism and social repression.

Mahour Jabbari.

Writer-director Sadaf Foroughi, here making her feature directing debut, initially shows the similarities a high-schooler in Tehran shares with her Western counterparts. The film opens with a drive to school, as Ava Vali (Mahour Jabbari) asks her mom, Bahar (Bahar Noohian), to let her off before they get to the front entrance. We initially think nothing of the mother's insistence that she gets inside the building immediately, but it turns out to be a harbinger of (very bad) things to come.

Ava and her parents live comfortably in a spacious, tastefully decorated home that here serves as a secondary character. Shifts in camera placement are minimal, as Foroughi opts to let most scenes play out in long shots with few cuts. It's an effective strategy, as we become a fly on the wall and listen in as Bahar, a doctor with a demanding schedule, confides to her husband Vahid (Vahid Aghapour), an architect who's often away, that she's considering cancelling violin lessons for Ava, who intends to pursue a career as a classical performer. “There's no future for her in music,” she tells her husband, who defends his 16-year-old daughter's impetus to follow her passion. The battle lines are thus drawn.

Mahour Jabbari, Bahar Noohian.

Emboldened by her refusal to even consider her mother's wishes, Ava pretends to go study with her best friend Melody (Shayesteh Sajadi), but instead sneaks out to hang out with Nima, the boy who accompanies her on the piano during her violin lessons and (let's be honest here) who she is nursing a crush on. Her decision to risk incurring her mother's wrath is ostensibly to win a bet against a classmate who's certain Ava doesn't have “game” in the dating department, but Foroughi suggests her resentment at home plays a role in her actions.

Leili Rashidi.

In a crucial miscalculation, the teens lose track of time, and by the time Ava races back to Melody's apartment, Bahar is having it out with Melody's (single) mother in loud, embarrassing fashion. That tense argument, captured in a beautifully composed long shot, lays bare Bahar's comtempt for a working woman of a more modest background who dares to (egads!) raise her children without a father. It's a skillfully staged scene.

Does Bahar punish Ava's disobedience by grounding her? Nope. She forces her to go to a gynecologist to make sure nothing has been tampered with in the nether regions. It all goes steadily downhill from there, as Foroughi follows the disintegration of this close-knit family unit with laserlike precision.

Vahid Aghapoor.

Things continue to deteriorate for Ava at school, where whispers of the teen's unaccompanied afternoon stroll reach the ears of the principal, Ms. Dehkhoda (Leili Rashidi). The school administrator, obsessed with saving face and determined to wash her hands of anything that would make her the target of government scrutiny, has already warned her students about the destructive scorn that befell a girl at another school who “brought a certain circumstance upon herself.” (It involves the birds and the bees, but there's no room in here for such unsavory remarks.)

Shunned by her classmates, Ava shuts herself off from even her dad, who plays good cop to Bahar's bad cop. And as we watch the downward spiral unfold, observant viewers will notice something curious about the screen's aspect ratio: it begins to shift. As the teen's woes grow increasingly dire for our protagonist, the frame becomes more and more rectangular, as the tighter compositions convey the girl's constricting outlook. Talk about tightening the vise.

What prevents “Ava,” a Canadian-Iranian-Qatari co-production, from being a tough sit is Foroughi's meticulous formal command of the medium, coupled with a steadfast refusal to vilify anyone. Not even the hissable Ms. Dehkhoda, whose bark turns out to be tougher than her bite. Rashidi tears into the juicy role with gusto, relishing the condescending finger-wagging she inflicts on her students. She runs away with every scene she's in.

Bahar Noohian, Mahour Jabbari.

But kudos are also in order for Jabbari, who does most of the heavy lifting on screen and handles the emotionally draining subject matter in confident, captivating fashion. If there's something I wish Foroughi could have done differently is tighten and pare down the shouting matches between Ava and her parents. The lacerating exchanges always ring true, but they become repetitive in a way that makes an otherwise well-paced film feel longer.

I also felt the strain from the director in that final shot, which, although far from identical, echoes that final freeze frame in François Truffaut's “The 400 Blows” in conveying the toll those growing pains take on a rebellious youth. Jabbari's nostrils flare as she breaks the fourth wall, but her story is told so affectingly that the moment is unnecessary. It's a rare overreach in a film that navigates its Orwellian territory with compassion and admirable urgency.

“Ava” is showing through Thursday, July 12 at the Miami Beach Cinematheque. For showtimes, go to www.mbcinema.com.