Ferenc Lengyel in "Curtiz."

The little festival that could is not so little anymore. Quite the contrary. Boasting 107 movies from 25 countries, the Miami Jewish Film Festival reaches its 23rd edition in jam-packed, full-throttle form befitting the hands-on, forward-thinking approach of executive director Igor Shteyrenberg.

Local cinephiles attending the frequently sold-out showings are about to dive into their first full week following Thursday's opening night gala and screenings on Saturday and Sunday. This reviewer works weekends, so for the past several days, I've lived vicariously through my friends and colleagues' festivalgoing experiences. In fact, the only challenging part of covering MJFF for local critics is the timing of the event. Most of us professional reporters of cinema have just wrapped up a monthlong movie viewing marathon in order to vote for our respective critics groups' awards. (My editor Michelle Solomon recently published a comprehensive article detailing the results of the 2019 Florida Film Critics Circle Awards. They turned out pretty good this year. Both of us will also be picking a winner as part of MJFF's Critics Award jury.)

So what can one say about this year's lineup? It's massive, eclectic and stubbornly hard to pigeonhole, as it should be. It features something for every moviegoer's sensibility and taste. Sure, there are generous helpings of acclaimed, highly touted productions, but there's also room for more commercially inclined offerings. It's an ideal balancing act for viewers like yours truly, who likes prestige stuff but also hungers for more populist fare. For example, the (unseen by me) Israeli espionage spoof “Mossad,” screening Monday and Thursday nights, promises the kind of lowbrow humor that, at least on paper, serves as a pleasantly junky chaser after a day of demanding arthouse content. Because sometimes you must give in to your cravings for brain-dead laughs, am I right?

Just as exciting is the way Shteyrenberg has paired new films with older titles that share particular connections with one another. For instance, a documentary about film composer Dave Grusin will be followed by a special screening of Richard Donner's “The Goonies,” the 1985 box office hit featuring, you guessed it, a score by Grusin. The older films will be screened for free on the Miami Beach SoundScape's 7,000-square-foot projection wall.

I'm sensing Shteyrenberg has a few surprises in store for festivalgoers. We'll just have to wait and see. In the meantime, here's a look at four selections showing this week. Three of them were made by Eastern European filmmakers and deal with subject matter where the region figures prominently. Three of them are most definitely worth your while. As for the dud in the bunch, well, you can't win 'em all, can you?

“Curtiz”: Let's rip off the Band-Aid right off the bat. This Hungarian production purports to chronicle the making of the wartime classic “Casablanca” from the point of view of its director, Hungarian Jew Michael Curtiz. It's shot in lush black and white, is awash in Golden Age Tinseltown trappings and is mindful of the political realities of the period. There's a commitment to portraying the prolific Curtiz in clear-eyed fashion, a willingness to explore his difficult nature, stern on-set demeanor and misogynist double standards. It finds in leading man Ferenc Lengyel a compelling figure with an uncanny resemblance to the man he is portraying.

Ferenc Lengyel in "Curtiz."

So why is it so lousy? Let's begin with director Tamás Yvan Topolánszky's failure to make his version of the Warner Bros. studio lot circa 1942 ring true. Scenes featuring American characters are often played by non-U.S. actors doing their best to sound like real McCoy. (They don't.) It doesn't help matters that the screenplay favors jarring, anachronistic dialogue that takes viewers out of the period. When asked why Ronald Reagan, who was originally set to star, is no longer attached to the project, one character says, “He told me he was going to make America great again.” At one point, WB mogul Jack Warner (Andrew Hefler) refers to “alternative facts.” Riiiiight.

But wait, what about the scenes featuring “Casablanca” stars Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman? The filmmaker shoots Bogart in fleeting chiaroscuro glimpses and Bergman in blink-and-you-missed-her soft focus. But despite voice actors David Miller and Anna Johnson's damnedest efforts to sound the part, the illusion crumbles like a house of cards. It would have helped if cinematographer Zoltan Devenyi had lensed the film in the 1.33 Academy aspect ratio used at the time, but his widescreen compositions feel conspicuously out of place here. It all amounts to an unconvincing facsimile of studio system strife.

At its core, the film centers around Curtiz's fraught relationship with Kitty (Evelin Dobos), his illegitimate daughter, who has talked her way into being cast as an extra on the troubled production and has even caught the eye of Johnson (Irish actor Declan Hannigan), an exec tasked with ensuring Curtiz keeps his World War II romance strictly pro-American. There's the germ of a good movie in the ebb and flow of the estranged father and daughter's bond, but Topolánszky is dead set in shoehorning parallels between Curtiz's life and that of his “Casablanca” characters, to the point where it drowns out everything else. His chronicle of this eventful period in Tinseltown history feels patently counterfeit, an amateurish foray into national identity and show business that fills its vacuous spaces with superfluous trivia. He's made a cheap imitation Louis Vuitton purse of a biopic, filled with Hollywood hand-me-downs.

(“Curtiz" screens Monday, Jan. 13 at 6 p.m., O Cinema South Beach, and Thursday, Jan. 16 at 2 p.m., Coral Gables Art Cinema.)

Yehuda Nahari Halevi, Daniella Kertesz in "Incitement."

“Incitement”: Here's a portrait of the past that feels uncannily accurate. This absorbing docudrama from Israeli filmmaker Yaron Zilberman (“A Late Quartet”) depicts a painful chapter in his country's history: the events leading up to the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on Nov. 4, 1995. What's bold and gripping about the film is not only that it's told through the point of view of the convicted shooter, law student Yigal Amir, but that it invites us to experience myriad aspects of his life in a way that doesn't even prioritize his budding extremism, at least not right away.

Amir, played by the charismatic Yehuda Nahari Halevi, looks at the evening news and shakes his head in indignation and disbelief. President Bill Clinton has just proclaimed a new period of harmony in the Middle East. (Remember that photo op with Rabin and Yasser Arafat? I certainly do.) A slap in the face is more like it, the strapping young man laments, his face a study in simmering resentment. But the twentysomething go-getter, born to an Orthodox Yemenite family, is bright, devout and caring. A good kid who studies hard and displays effortless leadership qualities. But with his darker features, he doesn't look Israeli to some (i.e. law enforcement), making him feel at times like a foreigner in his homeland.

Yehuda Nahari Halevi in "Incitement."

What propels this swiftly paced character study is witnessing Amir's transformation from good-natured role model into calculating terrorist. It speaks volumes about Zilberman's grasp of his subject that one ends up preferring the more harmonious scenes between Amir and his parents, Geula (Anat Ravnitzki) and Hagai (Yoav Levi), or his girlfriend Nava (Daniella Kertesz), than those depicting Amir assembling all the pieces he needs to set his dastardly plan into motion, though those moments are portrayed with sobering nonchalance. (Think of a more easygoing Costa-Gavras, or the work of Chilean director Pablo Larraín.) These, Zilberman conveys in nonjudgmental terms, are not the actions of an evil person, but of a misguided young man who thought he had the best interests of his country at heart, right up until the moment he pulled the trigger.

(“Incitement” screens Monday, Jan. 13 at 8:30 p.m., Miami Theater Center, and Tuesday, Jan. 14 at 8:30 p.m., Regal Cinemas South Beach.)

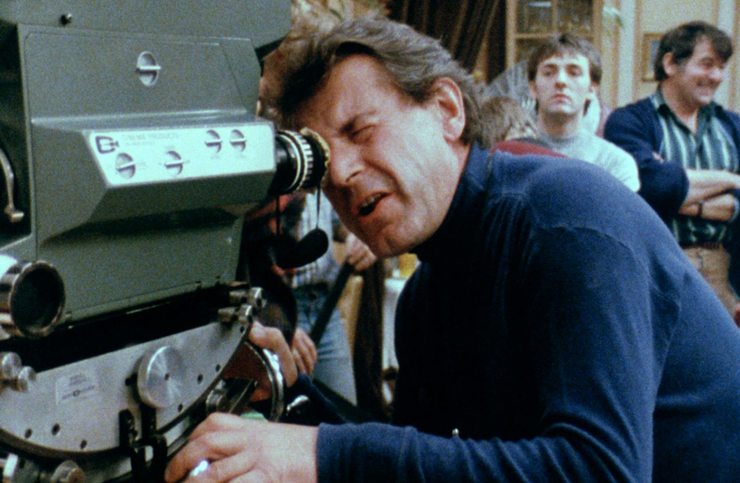

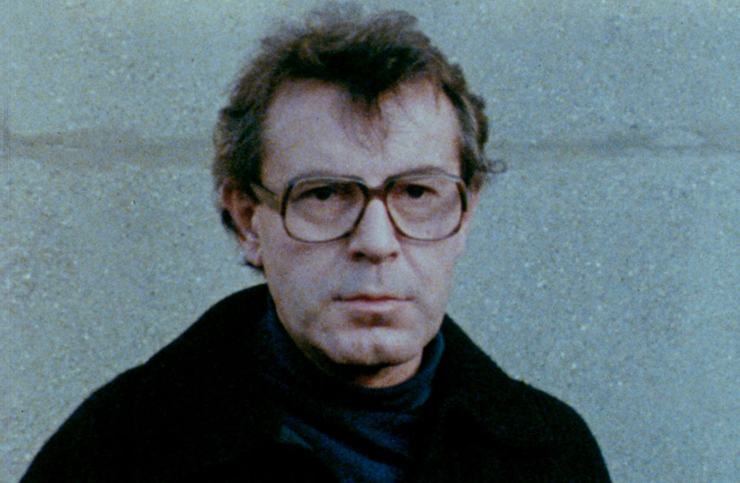

Milos Forman in "Forman vs. Forman."

“Forman vs. Forman”: If you can only make it to one movie this week, this richly insightful documentary on the legendary Czech director of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest,” “Amadeus” and the screen adaptation of the musical “Hair” should be at the very top of your itinerary. Hurtling forward like a runaway train, this riveting biography juggles interviews with the late Milos Forman at different intervals in his tumultuous, never boring career.

Directors Helena Trestíková and Jakub Hejna know they're dealing with an irrepressible force of nature, so they let Forman tell his story in his own words and stay out of the way. The first-person approach works like gangbusters, and not just because the twists and turns in the filmmaker's life feel like something out of a movie. He matter-of-factly states both of his parents died in concentration camps, then describes how his country transitioned rather quickly from fascism to communism. The films that came out while he was going to film school were designed to brainwash the masses. (“Full of idiocy,” he says with unvarnished candor.) It was from his own defiance about government-sanctioned propaganda that the Czech New Wave was born.

Milos Forman in "Forman vs. Forman."

“Forman vs. Forman” is the whole package, a portrait of the man and the artist that gives equal importance to what made his approach to filmmaking so special and to his personal trials and tribulations. You can detect a similar brutal honesty in the work of Werner Herzog, but Herzog has never made a film quite as glorious as “Amadeus.” The latter half of the documentary is devoted to Forman's life making movies across the pond, how the Hollywood establishment revered this maverick before turning its back on him when later works did not prove to be as popular as his earlier successes. At 78 minutes, it's a lightning bolt of a movie. It zips by in what feels like under an hour, and yet I have yet to see a more satisfying work from this year's MJFF crop. Don't miss it.

(“Forman vs. Forman” screens Wednesday, Jan. 15 at 6 p.m., O Cinema South Beach.)

Abigel Szoke, Karoly Hajduk in "Those Who Remained."

“Those Who Remained”: But I'm sensing that Hungary's official entry to the Academy Award for Best International Film is the MJFF selection that audiences will fall in love with, and it's easy to see why. This delicate and bittersweet look at wayward souls in post-World War II Budapest may not have the most dynamic visual style, but even though it doesn't quite break new ground in thematic or aesthetic terms, it gives us complex characters we can't help caring for, at least once they're done getting on our nerves.

Based on the novel by Zsuzsa F. Várkonyi, the film centers around the unlikely friendship that blossoms between gynecologist Aladár Korner (Károly Hajduk) and the rebellious and precocious Klára Wiener (Abigél Szoke), a teen brought as a patient by her great-aunt Olgi (Mari Nagy), who rescued the girl from an orphanage at age 11. Klára's combustible personality suggests she'd be the last person a plain, taciturn and soft-spoken man like Aladár would gravitate toward. (He resembles an elongated, sad-sack Robert Benigni, utterly devoid of joy.) But when the pesky 16-year-old's enervating ways lead her to the good doctor's doorstep, their ensuing relationship feels utterly believable. They might be damaged goods apart, but together, their lives attain something that resembles the normalcy they've been deprived of for far too long.

Abigel Szoke, Karoly Hajduk in "Those Who Remained."

Because what links this mismatched duo is the sting of personal loss. One of the film's most rewarding aspects is watching Klára peel back the layers concealed beneath Aladár's unassuming facade, and in turn witnessing Aladár patiently reining in Klára's self-destructive impulses. Most bracing of all is director and co-screenwriter Barnabás Tóth's ability to navigate how the characters grapple with their devotion to one another, emotional and physical, and how it arises suspicions in a society where people “disappeared” on a regular basis. It's a precarious tightrope the filmmaker is required to walk in handling subject matter that could easily turn salacious and icky in less assured hands. But deep affection for these two loners who bring each other back to life wins the day in “Those Who Remained,” a wistful and touching period piece that wears down your defenses and wrings tears that feel fully earned. Well done.

(“Those Who Remained” screens Wednesday, Jan. 15 at 8:30 p.m., Miami Theater Center, and Wednesday, Jan. 22 at 6 p.m., Miami Theater Center.)

The screenings of “Curtiz” and “Forman vs. Forman” will be followed by special free screenings of “Casablanca” and “Amadeus,” respectively, at Miami Beach SoundScape. For more information about tickets and showtimes, go to miamijewishfilmfestival.org/films/2020 or call 1-888-585-3456. I hope to see you at the movies.