It starts with that clear glass of water. More so than any of the iconic images it conjures up in our collective subconscious, those foreboding ripples immediately come to mind whenever I think of the first Jurassic Park. They sent chills through this viewer's body more effectively than any of the pioneering CGI that knocked moviegoers' socks off back in the summer of '93.

That simple yet inspired tactic also popped into my head while seeing Jurassic World at a packed advance screening last week … mostly because such low-key inventiveness was nowhere in sight. The newly crowned box office champ its $208.8 million debut in the U.S. dethroned Marvel's The Avengers for biggest domestic opening weekend – profited off of intergenerational nostalgia for the original and our timeless fascination with dinosaurs, but it's not because it proves itself a worthy successor to Steven Spielberg's solid (yet hardly career-best) adaptation of Michael Crichton's bestseller.

If anything, it sullies the franchise's cultural legacy by reining in its capacity to get under your skin. It domesticates the demons a monster mash of its kind ought to unleash to keep you up at night. In short, it retrofits the franchise for consumption of millennials who like their pop culture slick, tame and utterly toothless. Worst of all, long stretches of it are boring.

LEFT: (from left): Bryce Dallas Howard, Chris Pratt, Nick Robinson, Ty Simpkins, RIGHT: Chris Pratt.

It would be nice to report director Colin Trevorrow, who made headlines for landing the coveted gig on the strength of his indie debut feature, the charming sci-fi-flavored rom-com Safety Not Guaranteed, attempted to chart his own path and make us forget about the previous entries in the saga. Thing is, Jurassic World makes it a point to keep reminding us.

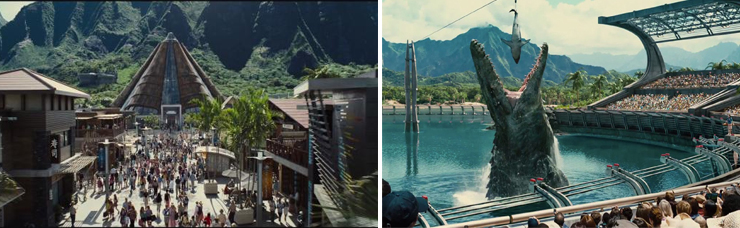

It's been 22 years since human greed triggered a chain reaction that set cloned prehistoric beasties loose on Central America's Isla Nublar. Rather than allowing three movies' worth of bloodbaths deter moneyed capitalists from investing in a rebirth of the ill-fated theme park, the opposite has happened. In the two decades since a pissed off T. Rex chased after Jeff Goldblum's quip-happy mathematician, owner Simon Masrani (Life of Pi's Irrfan Khan) shepherded its journey from failed science experiment to thriving destination for the well-to-do. (Product placement includes Pandora Jewelry, and yes, there's a Starbucks on the premises.) Running the show is high-strung go-getter Claire Dearing (Bryce Dallas Howard), who is freaking out over the impending debut of the Indominus Rex, a bigger, meaner dino hybid.

It doesn't take long for Owen's doomsday scenario to become a reality, Ms. Indomina all the dino clones are female has outsmarted the techie drones minding the store and sets upon a blood-soaked trajectory to reach the actual theme park area, a pot o' gold of human flesh to feast upon. It's up to stoic Owen and pent-up Claire to stop the sharp-toothed creature before her shenanigans bring upon financial ruin. Oh, and all that potential loss of human life's no bueno, either.

RIGHT: (from left): Chris Pratt, Bryce Dallas Howard, Omar Sy, Vincent D'Onofrio.

But who cares about who lives or dies in this antiseptic World when the closest thing the movie has to sacrificial lambs are Claire's annoying nephews? Zach Mitchell (Nick Robinson) and baby bro Gray (Ty Simpkins) are Trevorrow and his screenwriting team's way of establishing just how emotionally stunted Claire has become. (As if viewers might miss this, several scenes engage in what I like to call frigid shaming. We get it. Claire needs to mellow out.)

The kids also occupy significant screen time to justify recycling JP's justly celebrated sequence in which a curious T. Rex attempts to wiggle out the original park creator's grandchildren from their tour jeep. That scene worked because Spielberg forced you to feel the children's horror at being this dinosaur's prey. Remember that long shot that shows the kids screaming in terror as Ms. Rex stomped on the overturned vehicle? It was visceral and unpleasant, and all the stronger for it. By contrast, the new movie's equivalent pits the Mitchell kids against Indominus with a bubble-shaped rail car standing between them. A fleeting moment, in which some other dinosaurs kick the high-tech vehicle like a marble, possesses a smidgen of Spielberg's visual flair, but the ensuing attack is a wash; it's inert and perfunctorily staged. I was rooting for the brats to become a snack.

LEFT: Chris Pratt, RIGHT: Irrfan Khan.

Of all the many disappointing elements in Trevorrow's by-the-numbers retread, none is more soul-crushing than the way it treats the velociraptors, the original film's most memorable scene-stealers aside from Goldblum's chaos theorist, naturally. A tense moment early on that has Pratt's character stepping into the pen and confronting the vicious carnivores gives way to the myth of the noble raptor, and the creatures change allegiances so many times it's whiplash-inducing. It's symptomatic of the screenplay's tendency to pull the film in different directions at once, thus preventing it from achieving aesthetic and thematic cohesion. It's a lamentable case of too many cooks in the kitchen, and it cuts off Trevorrow's creativity, which was in wide display in Safety Not Guaranteed, at the knees.

To add insult to injury, Jurassic World relegates its iconic T. Rex to a bit player that gets trotted out when the going gets tough, and then it pretends she was a significant element of the film all along. But Trevorrow is too busy making a point about theme park culture and movie sequels to make us feel the slightest bit of suspense.

He may have earned a coveted entry on his résumé, but in the process he fetishizes the very setting he purports to depict with a critical eye, giving mayhem-hungry crowds what they want, but not the transgressive carnage they need. He's made a tentpole title that makes a dent in our wallets without leaving much of a footprint in our dreams.